JOHN CALE: “I’m a classical composer, disheveling my musical personality by dabbling in rock and roll.”

NAT FINKELSTEIN:

“John Cale is a fucking elitist. He did not like the people he was playing for.

He’s Welsh, and they’re all nasty bastards.”

JONATHAN

RICHMAN: “Folks like to imbibe simulated darkness and decadence, when a guy

like John Cale can give them the real thing using only chords, tones and

textures.”

JUDY NYLON:

“John was charismatic with no feminine aspects to his face… one of the very few

guys around that could be honestly called ‘handsome.’ He was smart and

impatient… an art monk outsider with more energy than outlets… an intuitive

Celtic poet whose work was like a telepathic electric bolt that rarely misses

its mark.”

TIM MITCHELL:

“By now Cale’s New York lifestyle, with Betsey gone, had become claustrophobic

and deadening, and he jumped at an offer from Joe Boyd to work with him on film

music at Warner Brothers Records headquarters in Los Angeles… Early in 1971

Cale forsook New York and heroin for Los Angeles and cocaine. As soon as he

walked into the Warner Brothers offices there, the smell of pharmaceuticals was

in the air and it was to prove an irresistible lure.”

PETER HOGAN:

“Newly divorced from Betsey Johnson, Cale soon became involved with Cindy

Wells, a.k.a. ‘Miss Cindy’ of the Frank Zappa-sponsored group the GTOs, who had

broken up the year before. Wells was evidently unstable – a former groupie,

she’d had an illegitimate child by Jimmy Page in her teens. The couple were

married soon after, and the union was a disaster almost from the start – Cale

later described it as ‘the most destructive relationship I ever had.’ After her

bandmate Miss Christine died from a drug overdose in 1972, Cindy plunged into

serious depression and hysteria – to the point that Cale had her committed on

the recommendation of a psychiatrist. Meanwhile, he’d developed new substance

problems himself, this time with alcohol and cocaine.”

MISS CINDY: “I’m

the chronic liar of the GTOs… I can’t remember anything… I don’t know how old I

am, I’m from everywhere.”

TIM MITCHELL:

“When Cale married Cindy, a few months after meeting her, he was making a

doomed attempt to give some stability to an irredeemably imbalanced

personality, and the effort would draw deeply upon his own reserves of

strength. For the marriage ceremony he had originally expressed a desire to be

dressed in tennis gear, the sport having become a regular recreation of his,

while he recited the vows in imitation of a polar bear and Cindy pretended to

be a dog.”

TIM MITCHELL:

“After the wedding Cale and Cindy moved into their own house in the San Fernando

Valley. On one occasion Cindy went out shopping and Chris Thomas was left at

home with Cale. The phone rang and Cale asked Thomas to get it. Hearing what he

thought was a familiar female voice on the other end, Thomas was surprised to

be asked to pick the caller up from the airport and replied that he thought she

had only gone shopping. Once the phone call had become bogged down in

non-sequiturs, Thomas handed the receiver to Cale, saying that he could not

figure out what Cindy was going on about. Cale took over the call and

discovered that it was actually Nico on the phone – and Thomas realized where

Cindy had got her unusual speaking voice.”

JOHN CALE: “My

second wife, Cindy, met me in Ibiza with a walking stick filled with cocaine.

It soon became evident that she was dispensing it liberally everywhere she

went… I followed her to the dock area. I had been drinking so I got really loud

with her. I said, ‘have you been taking heroin again, darling?’ at the top of

my lungs, very Noel Coward… She leaped up and ran off, but all I had to do to

track her down was follow the sounds of commotion and distress. I finally

pinned her down in the middle of the street with a suitcase in her hand,

whirling around in circles.”

TIM MITCHELL:

“Towards the end of the ‘Paris, 1919’ sessions, with much of the work done and

the results pleasing, Cale began to indulge himself a little more. On one

occasion, coming out of the Japanese restaurant underneath the Chateau Marmont

where Chris Thomas was staying, he and Thomas waited for their dinner guests to

emerge. Thomas sat on the bonnet of Cale’s Shelby Mustage, and Cale began

driving him slowly round the car park. Before Thomas knew what was happening

they were out on Sunset Boulevard and Cale was accelerating fast, with his

producer grimly holding on to the bonnet vents. After a mile Cale turned the

care round and drove him back again. Thomas was convinced he was going to die.

By the next day he had pulled himself together enough to make a furious phone

call to Cale, shouting at him: ‘Do you realize you could have killed me?’ ‘Do

you realize I could have lost my license?’ Cale replied.”

TIM MITCHELL: “On another occasion Cale drove Chris Thomas to Santa Monica in roughly eight minutes, a journey that Thomas remembers as ‘seriously terrifying’ and ‘probably impossible – even if you go by spaceship.’ Despite this, Cale was unsatisfied with the Mustang and wanted something faster. Still new to driving, another worrying habit of his was to keep the car in second gear most of the time.”

JOHN CALE: “After Cindy left London I was sitting around talking with Brian Eno and getting drunk when she called me from L.A. A girlfriend of Cindy’s who was a nymphomaniac had come to London and was sitting there with Brian Eno. She started giggling very loudly so that Cindy would hear her over the phone. I snapped. I went completely berserk. I was holding a shot glass and I went THWUMP and knocked all her teeth out… She ran out, but came back later that night and fucked me with her broken teeth. Then she claimed she was pregnant… In the meantime Cindy had been arrested. For the past week, it transpired, my wife had been spending time with a man who was under surveillance by the Regional Crime Squad for his role as the driver of the getaway car in the famous Great Train Robbery of 1963.”

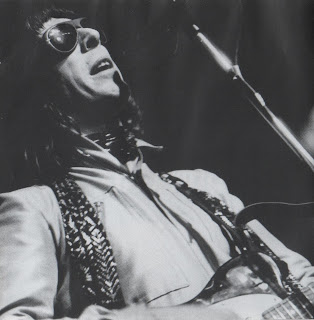

MICK GOLD: “The

man, John Cale, seemed far removed from the music he was making, watching with

dispassionate interest as an audience of sixteen year old maniacs covered in

glitter flicked lighted matches at each other and fell on their stoned faces in

an eerie acting out of the VU’s themes of juvenile corruption.”

JOHN CALE:

“Resentment and paranoia filled those days. Interviews were irritable and

fractured, performances such as one in the amphitheatre in Orange on the French

tour, would collapse when I flashed the audience, ran off stage, and even out

of the amphitheatre. Being without my pass, I was not recognized and let back

in.”

SEAN O’HAGEN: “I

find John Cale fascinating insofar as he could actually write a happy song but

still convey an element of malice.”

TIM MITCHELL:

“The show at the Victoria Palace was scheduled to take place on 22 September

and feature the St. Paul’s Cathedral Boys’ Choir on a version of the Beach

Boys’ ‘Surf’s Up.’ There would also be a performance of the yet-to-be-released

‘Guts’ that would feature half a side of beef held by two assistants in lab

coats. Cale was to illustrate the song by pointing to various parts of the cow,

and the song would end with him throwing the contents of a bucket of entrails

at the audience. The show was postponed and never rearranged.”

LEEE BLACK

CHILDERS: “I was staying at the Tropicana Hotel in Hollywood. One day we heard

all this noise. We looked across the parking lot to the other side where the

noise was coming from and suddenly the whole door of this room came flying out

onto the balcony, and there stood John Cale. He couldn’t work the doorknob, so

he just knocked the door down, right off the hinges.”

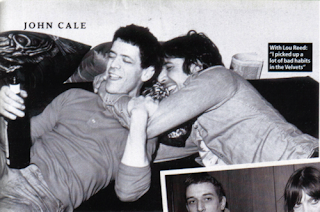

DEERFRANCE: “On

the road, or in New York, John could be very scary. But I always thought Lou

Reed was scarier. Lou was totally cold, almost inhuman whereas John did have

quite a lot of humanity."

PETER HOGAN:

“Touring would become increasingly important to Cale – he thrived on the

uncertainty of it all, and the income was vital. Live, he adopted a range of

costume disguises that included ski goggles and a hockey mask. Some nights he

appeared swathed in bandages, looking like The Invisible Man. His performances

became more theatrical and improvised, conjuring up an atmosphere of seething

violence and paranoia. One night Cale broke some fake blood capsules concealed

in the crotch of a human dummy, and played the remainder of the gig covered in

bloodstains. Cale had always been fascinated by gore, and even in his youth had

paid visits to the local abattoir. The fascination reached a peak at a gig in

Croydon in early 1977, when Cale hacked the head off a chicken he’d killed

earlier and tossed its carcass into the audience. Half his band quit in protest.”

CHRIS SPEDDING:

“I didn’t even know who John Cale was when I got the call to do the ‘Slow

Dazzle’ session. I only got to find out about the Velvet Underground later on.

Working with John wasn’t straightforward, but I like that sort of challenge:

‘Let’s do it in a different key.’ ‘Let’s do a different tempo.’ John wanted to

inject something new into the recording process. I knew him when he had a

reputation for doing crazy things on stage, like the incident involving a

chicken. It wasn’t long after I’d finished playing with him, and he called me

up from America. It was after a gig one night, and he asked if I knew any

drummers. I said: ‘Oh John, what have you done?’ And he went: ‘Well, I kind of

bit a chicken’s head off on stage and my drummer’s a vegetarian. He’s refused

to play with me anymore.’”

LEEE BLACK

CHILDERS: “I liked John personally and we got up to all kinds of adventures. I

remember once I hid his whole band at our flat in Oakley Street, London. It was

when the weird rumors were going round that he was biting the heads off

chickens and things like that. He did do something on stage, but I can’t

remember what it was. In any case, his band were all vegetarians. They showed

up at my flat in the middle of the night and said, ‘Can you hide us from John?

We’ve left the band, we’re hiding out.’ So I took them in and hid them. He came

to the house and looked in through the window, but the band were all huddled

behind a column on the other side of the living room so he couldn’t see them.

He knocked at the door. I answered and told him, ‘They’re not here and we’re

all asleep.’ He knew they were there. ‘Let me in!’ he said. ‘No,’ I said. He

laughed about it later.”

TIM MITCHELL:

“The tour, playing mainly theaters, was a big success with audiences and went

off relatively smoothly – despite the band having been warned beforehand that

Cale had an almost schizophrenic ‘split personality.’ In Brussels, early on in

the tour, the after-show conversation, which had been on the subject of the

night’s gig, changed as if at the flick of a switch. Cale’s facial expression

darkened, and his voice dropped low as he asked: ‘Do you know what a rocket is?

Do you know what a rocket is? It’s what is left behind…’ Later that night, on

the stairs of the band’s hotel, Cale made a noisy appearance, naked, with a

frightened looking Jane Friedman. The band pulled her into a bedroom and locked

Cale out, but he opened a window in the hall, hauled himself through and

climbed from balcony to balcony until he was outside the room. It had been

raining; Cale stood with one bare foot in a pool of water and the other planted

right next to the transformer for the neon lights of the hotel. Jane was

ushered out of the room and Cale dragged in – literally inches from death. From

this point on, he became known on the tour as ‘the Fiddler on the Roof.’”

JOHN CALE: “I was in Holland doing a radio interview and I’d got pissed in the afternoon, so by the time I came to the interview I was totally out of it. The guy said, ‘I’d like to ask you a few questions,’ and I said ‘sod off you bastard.’ I started punching him and he slapped my face. All this went out on the air. Afterward I got a letter from the company saying that I wouldn’t have felt a thing if they’d performed major surgery on me.”

CHRIS CARR: “He had a very rock’n’roll reputation at the time, but always with this kind of quality. John was a brandy man and John was a coke fiend in those days, and there are all these legendary stories… Spedding tells the story of getting into Colchester and John was desperate for a line because his parents were in the audience that night, so he did a line of chalk without realizing it.”

PATTI SMITH: “My picking John as a producer was about as arbitrary as picking Rimbaud as a hero. I saw the cover of ‘Illuminations’ with Rimbaud’s face, y’know, he looked so cool, just like Bob Dylan. So Rimbaud became my favorite poet. I looked at the cover of ‘Fear’ and I said, ‘Now there’s a set of cheekbones…’ The thing is, in my mind I picked him because his records sounded good. But I hired the wrong guy. All I was really looking for was a technical person. Instead, I got a total maniac artist. I went to pick out an expensive watercolor painting and instead I got a mirror.”

DAVE THOMPSON:

“A few weeks before the first studio date, Cale had Jane Friedman book the

group a show in Woodstock so he could see them perform away from their usual

audience. A small and unsuspecting audience stared in disbelief as Cale missed

most of the first set when he passed out at the side of the stage. He came to

in time for the second set, but spent a lot of that throwing up. ‘That meant

the second set was better than the first,’ Cale excused himself afterward.”

TIM MITCHELL:

“’Horses’ would not only be another important entry in Cale’s producer’s CV, in

the same column as the Nico projects and the Stooges and Modern Lovers albums,

but would also mark a new development for him. Here Cale got Patti Smith to

reinvent her poetry as a new form of rock’n’roll, and the result was one of the

landmark albums of the 1970s. On at least one occasion during the sessions the

verbal battles between Cale and Smith over the form of the album turned

physical, with Smith hitting Cale. He was also seen crawling along the floor

and head-butting a wall.”

NICO: “John

always reacts well to strong women. I don’t know what kind of relationship he

had with them outside of the studio. But in the studio it is a physical thing,

sexual, John pushing toward his orgasm and the woman pushing toward hers. On my

albums we were like two lovers even when we weren’t lovers. You can hear it in

the arrangements – we are fighting for our own satisfaction but pushing for

each other’s as well. It was the same when he worked with Judy Nylon and

Deerfrance and it was the same when he was working with Patti. They fought like

animals, but the music sounded like they were fucking like animals as well.

Patti should have married John. They could live in a gingerbread house and make

gingerbread children.”

CHRIS SPEDDING:

“I could never figure out was the first line of the song ‘Guts’ was. He always

seemed to garble it. But one night his parents came to Cardiff and sat by the

side of the stage and I heard it clearly for the first time: ‘The bugger in the

short sleeves fucked my wife, did it quick then split.’ And I was just looking

at his nice mother and father, this elderly couple, thinking ‘I wonder if they

heard that?’”

TIM MITCHELL:

“The New York that Cale immersed himself in was one steeped in politics and

political intrigue, guns and missiles, mercenaries, terrorism, espionage and

the ongoing Cold War. He subscribed to a variety of publications unavailable on

newsstands, including mercenary magazines – the kind of thing that would arrive

through the post in photocopied form, mailing lists for these magazines

attracted the attention of the CIA, and Cale appeared on their files as a

result. This fact bore out his claims to have been followed by them – being

paranoid did not mean that they were not out to get him. Cale had been fascinated

by the CIA’s involvement with LSD production and experimentation in the 1960s.

Its ongoing, wider activities – particularly in destabilizing foreign countries

– would continue to absorb much of his thinking. He was also developing a

network of personal and correspondent contacts who were informed about the

subjects in which he was interested and through whom he would collect and trade

current information from all parts of the world. Cale’s concerns ranges far and

wide – wherever the cutting edge of world affairs could be found. In later

years he would know about AIDS from New York mortuary personnel while it was

still being diagnosed as ‘Green Monkey Disease’ and would predict both the

eruption of the Iran-Contra affair and the start of the Gulf War months before

they happened. Many people would go on to regret their tendency to doubt his

information and to put his theories down to paranoia.”

TIM MITCHELL: “One particular point of contact that Cale and Mike Thorne had was in the field of nuclear physics – more specifically, for Cale, the way to construct a nuclear bomb. A game of ‘raising the stakes’ developed. Cale had bought a nuclear textbook, and he showed it to Thorne, asking to be brought up to speed on creating a small device. Thorne paused and said thoughtfully: ‘Well, we’re going to need a few things.’ He explained that the main ingredients were a few pounds of plutonium and a critical mass and that the idea was for the two to come together suddenly – but not while the bomber was within a hundred miles. The engineering involved was very clever, but it would certainly be possible for a renegade state, with a lot of hard work and dedication, to make a powerful ‘dirty bomb’ and bring it into New York in something no larger than a suitcase. Cale decided that the project would be too time-consuming to be a practical consideration but that a successful end result might be a piece of performance art that could be jettisoned once it had been made.”

TIM MITCHELL:

“After a Dutch gig they found themselves in a bar in Leuven, and Cale got into

an argument that turned into a fight, during which a broken bottle was

produced. Cale fell on to the floor and landed on the bottle, the glass

puncturing not just his skin but, more important to him, the brand new pair of

leather trousers he was wearing. Thomas escorted him to the hospital, where, as

a doctor stitched him up, Cale ‘howled’ but meanwhile noticed something on the

shelf on the other side of the room. When the doctor left, Cale said to Thomas:

‘See that shelf up there? Get some of those bottles.’ Thomas weighed up the

probability of getting caught, having his passport confiscated and ending up in

jail, called on his Dutch courage and grabbed the bottles. The next day the

band were back in the van, driving to Brussels for a television performance in

the afternoon and rubbing the stolen Xylocaine into their gums, hoping that it

would enhance their journey. As they piled out of the van in Brussels the

television director came over and attempted to engage them in conversation, but

all he could get out of them were paralyzed mumbles. Mouths frozen solid, none

of them could get out a single intelligible word.”

TIM MITCHELL:

“Cale was usually a congenial travelling companion, interesting and witty, but

there were occasions, as on earlier tours, when it was best to stay out of his

way. Sometimes this was also advisable when Cale was in a cheerful frame of

mind… One night David Young was asleep in his hotel room when Cale crept in.

Sneaking up to the bed, Cale leaned over the somnolent guitarist and blew a

strawful of cocaine up his nose. Exploding suddenly into consciousness, Young

screamed at his gleeful attacker. The next day Cale rang Young to say that he

owed him ten dollars. ‘What for?’ ‘The line!’”

TIM MITCHELL:

“The Drury Lane gig marked the first appearance of what would briefly become a

Cale trademark: a white plastic ice hockey mask which, with two eye-sockets and

a grid of holes over the lower face, gave the wearer a distinctly horrifying aspect.

Cale had been interested in wearing masks on stage ever since his Velvet

Underground days. Adding a layer of mystery, they were also, like dark glasses,

a way of hiding from the audience.”

JAMES YOUNG:

“John Cale plunged into Dids’ miniature elf’s lair in Balham. Overweight,

overcoat, over here. Hiding his wild coke-starey eyes beneath scratched

Wayfarers, covering his beer-barrel gut with a stained sweatshirt and a

No-Smoking sticker. This was the man who’d directed the aesthetic of New York’s

most stylish pop group. Distanced now, by more than a decade, from the

marketing genius of Warhol and the savvy of Reed, he’d had to take on the

narcotic, alcoholic and psychic abuse alone… Dids’ living room was suddenly

full of him. He commandeered the coffee-table, emptied a wrap of coke, and

carved out four massive lines – one for me, one for Dids and two for himself. I

don’t think we’d even said ‘Hello.’ The ambience shifted abruptly from smack to

booze. Beer crates were stacked in the kitchen, six-packs chilling in the

once-empty fridge, bottles of vodka abandoned where they dropped.”

JAMES YOUNG:

“Over the following few days, Cale rambled a broken monologue, referring to

things he may or may not have mentioned previously. Blurred by booze, confused

by coke, it was hard to follow the sudden leaps of association. I got caught in

his mad Welsh rhapsody. He loved to talk plots and intrigues. Paranoid

conspiracy theories were his brain food. I’d be on the edge of sleep, when

there’d be a knock at my door: ‘James! Wake up! Listen! It says here that

terrorist groups in Europe are being covertly funded by powerful economic

interests in the U.S., in order to prolong European disunity and subordination

to the power of the dollar. What d’you think of that then, eh?’ He’d wait for

an answer. A paranoid insomniac with a bottle of Stolichnaya in one hand and a

wrap of coke in the other.”

JAMES YOUNG:

“Wherever you sat an empty bottle would alert you to Cale’s presence. He turned

the studio up-side down, making it his own. ‘Now, doant discuss anything of

what goes on in here,’ (the spies) ‘Pass a beer! There’s a squeak on the bass

drum pedal.’ (Swigs beer) ‘Gimme that blade!’ (Chop. Chop. Chop.) ‘Got a note?’

(sniffs) ‘…HMNYEAH…’ (pockets note). The delivery boy would arrive with beer

and champagne. Coke dealers would slither in and out. Cale’s manager, Dan

Saliva, would come in, a supercilious sneer on his face, jangling his keys,

wincing at the Teutonic cacophony, suggesting we do a Jim Morrison song. ‘Think

of America, John, think of America.’ Cale would stagger off into the night,

looking for some action, banging on the doors of some low rent bacchanal,

demanding to be admitted. Back in Brixton Cale couldn’t/wouldn’t sleep. He’d

blunder around the flat all night long, playing endless mixes on a ghetto

blaster. Nico gave him a shot to knock him out, he was bugging us so badly.”

TIM MITCHELL:

“On the first European dates earlier in the tour Nico had supported Cale, and

she and Chris Thomas had ‘hooked up together.’ Thomas had stayed with Nico in

Paris afterwards, and Cale had phoned him there in order to summon him back to

England for rehearsals. When he did return, it turned out that there was no

rehearsal – Cale had a proprietorial attitude to Nico that did not sit well

with her having relationships with members of his bands. Thomas remembers

meeting up with Lou Reed around that time and thinking that he sounded just

like Cale and Nico and that they must have taught each other to ‘play this

particular game.’ He told Reed that he spoke just like his fellow ex-members of

the Velvet Underground, and Reed replied: ‘Yes, but there’s one difference.

I’ve got talent.’”

JOHN CALE: “The

biggest problem I had was that I hated myself so much. I tried to mask any part

of my personality that was visible and dazzle with something else.”

JOHN CALE: “I

felt there was a certain kind of heroism in my way of life. The heroic stance

is to batter yourself with drugs and alcohol and still be able to stand up. And

you can, but you find that the law of diminishing returns comes around with a

vengeance… It was like trying to sort out your business and your personal life

in the middle of an earthquake.”