DAVID MEYER: “The Stones were in flux. Their musical direction was slightly uncertain. Their venture into psychedelia, November 1967’s ‘Their Satanic Majesties Request,’ was a forced effort and sold poorly. The band regarded it as an unsuccessful sellout, a mistaken side step from playing the music they knew and loved. Psychedelia did not suit them. The Stones, in ethos and expression, were not hippies. Peace and love were not their métier. The Stones moved toward a darker, blues-based, stripped-down, acoustic sound for their next album, November 1968’s ‘Beggar’s Banquet.’”

KEITH RICHARDS: “Politics came for us whether we liked it or not, once in the odd personage of Jean-Luc Godard, the great French cinematic innovator. He somehow got fascinated with what was happening in London in that year, and he wanted to do something wildly different from what he had done before. He probably took a few things he shouldn’t have, not being used to it, just to get himself in the mood. Nobody, I think, has ever quite honestly been able to figure out what the hell he was aiming at.”

MARSHALL CHESS: “Let me tell you, I think there was magic involved. The music is what hooked me and kept me around. There was magic there, all right. When we would be recording, we would go three days, four days, three weeks, nothing happened, not a track laid down. Then all of a sudden one night, magic would happen. Four or five basic rhythm tracks would emerge out of nowhere, utterly amazing, the whole band playing as one, the kind of thing only a magical combination of musicians can achieve. I had heard the same thing before at Chess Records, when that great creative thing happens – that’s my buzz.”

STEPHEN DAVIS: “Earlier in the year, Marianne had given Mick a copy of ‘The Master and Margarita,’ a newly translated novel by the Russian author Mikhail Bulgakov. Mick read it in his study in Chester Square, absorbed in the horrific story of the devil’s visit to Moscow in the 1930s in the company of a naked female vampire and a cigar-smoking black cat who’s a dead shot with a .45 Browning. Omnipotent, well-spoken Lucifer kills people, drives them mad, spirits others to distant places… Out of this came ‘The Devil is My Name,’ a lyric Mick took into Olympic Studio the week of June 4, when the Rolling Stones were filmed in rehearsal by Jean-Luc Godard for his hotly anticipated new radical propaganda film, ‘One Plus One.’”

ZACHARY LAZAR: “Mick’s new songs were all Devil songs in one way or another. Perhaps the Lucifer film was something to help him fill out this new role, the role of Mick – the Prince of Darkness, the Angel of Light, it wasn’t easy to tell the difference anymore. It was a role Mick had stumbled into, not exactly chosen, but it was also a role that practically nobody else could have even attempted. Brian had been preparing for it his whole life, and you could see it eating him from the inside, the dream that had come true but not in any of the ways he’d expected.”

PATTI SMITH: “Brian was a length ahead. He was gonna dig up the great African root and pump it like gas into every Stones hit. But it wasn’t time yet. Unlucky horoscope. Imagination and realization were ticking on separate timepieces. But Brian was in a hurry. Running neck and neck with his vision was his demon. Shove pins in the heads of innocents. Torn between evil energy and pure spirit. Bad seed with a golden spleen. The Stones were moving toward a mortal mergence of the unspoken monument and the hot dance of life. But they were moving too slow for Brian. So slow he split. In two.”

KENNETH ANGER: “Mick is a terrific skeptic, but one percent of him is superstitious.”

MARIANNE FAITHFULL: “Kenneth Anger had a huge and very conscious influence on the Stones. I think he thought Mick and the rest of the group could embody his vision.”

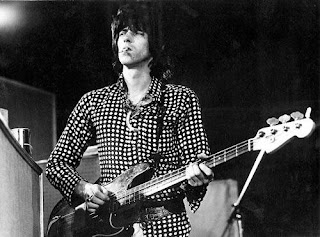

KEITH RICHARDS: “Brian would be down on his back, lying around the studio with his guitar strapped around him. Then he would contribute amazing things. Suddenly, from nine hours of lying there (or often not being at the sessions at all for two or three days, which would really get up everybody’s back), he’d just walk in and lay some beautiful things down on track, something that nobody’d even thought of.”

KEITH RICHARDS: “Man, when Brian wanted to play, he could play his ass off, that cat. To get him to do it, especially later on, was another thing. In the studio, for instance, to try and get Brian to play was such a hassle that eventually on a lot of those records that people think are the Stones, it’s me overdubbing three guitars and Brian zonked out on the floor. When things were getting really difficult, Brian would go out and meet a lot of people, before we did, because Mick and I spent most of our time writing. He’d go out and get high somewhere, get smashed. We’d say, ‘Look, we got a session tomorrow, man, got to keep it together.’ He’d come, completely out of his head, and zonk out on the floor with his guitar over him. So we started overdubbing, which was a drag cause it meant the whole band wasn’t playing.”

STANLEY BOOTH: "We listened to the Stones' first EP, then their second single, 'I Wanna Be Your Man,' with Brian's remarkable solo. Charlie was sitting on the couch with his back to the window, the lights of Los Angeles below. Keith flopped beside him. 'What happened to Brian?' Charlie asked. 'He did himself in,' Keith said. 'He had to outdo everybody, do more. If everybody was taking a thousand mikes of acid he'd take two thousand of STP. He did himself in.' Charlie nodded sadly. 'It's a shame,' he said. 'Brian could do that' - nodding toward the record player - 'without even trying.'"

MARIANNE FAITHFULL: “In a way, Brian Jones was George Harrison’s counterpart in the Stones. But there was a big difference in their personalities. The thing about George – and we all feel it strongly now that he’s gone off and left us – is that he plunged into things. Whatever he got into, whether it was the sitar and Ravi Shankar or the Maharishi, he walked right in and never looked back, and that takes a lot of confidence. Brian, on the other hand, was all flash. He loved to astonish – and then on to the next thing. Sometimes I’d get the eerie feeling that – like the positive and negative in a photograph – George was the positive version of Brian. They were quite similar in many ways; both could play a lot of different instruments and were hugely talented. But of course one difference was that Brian was unable to write songs. His perpetual upsetness and unhappiness and paranoia and low self-esteem all worked against him. It was tragic because he wanted to be a songwriter more than anything. I’ve watched the painful process, Brian mumbling out a few words to a twelve-bar blues riff and then throwing his guitar down in frustration.”

BILL WYMAN: “But, listen, Brian was okay. He was a very nice guy sometimes. But sometimes he was a real shit, it depended on his moods. At a given moment, he could be really, really evil if he wanted to be, but for the rest of the week he could be great, fun, enjoyable.”

ROBERT PALMER: “[Brian’s work on ‘Beggar’s Banquet] did not sound remotely like that of any other musician – black, white, living or dead. In black folk culture slide playing has always spoken volumes. He must have outdone himself on ‘No Expectations,’ because the song’s story was his story, the feelings his feelings, as he could never have expressed them himself.”

KEITH RICHARDS: “Godard at least managed to set Olympic Studios on fire. Studio one, where we were playing, used to be a cinema. To diffuse the light, he had tissue paper taped up under these very hot lights on the ceiling. And halfway through – I think there are some outtakes where you can actually see this – all of this tissue paper and the whole ceiling caught alight at ferocious speed. It was like being inside the Hindenburg. All of that heavy light rigging started to crash to the floor because it had burned through the cables; lights going out, sparks. Talk about sympathy for the fucking devil.”

VICTOR BOCKRIS: “The ‘Beggars Banquet’ sessions owed more than a little to the influences of Marianne Faithfull and Anita Pallenberg. Marianne opened a whole new world to Jagger: she gave him books; suggested songs he cover, such as Robert Johnson’s ‘Love In Vain;’ and wrote songs with him, such as ‘Sister Morphine.’ Anita had an even more profound effect. In the opinion of a number of people in the Stones’ entourage, during the ‘Beggars Banquet’ sessions Anita became a Rolling Stone, bringing to the band an influence as unsettling and creative as Jones had. She kept everything unbalanced and everyone on edge, following William Blake’s dictum that rules were made to be broken. Anita lit a fire under the naturally lazy Keith.”

IAN STEWART: “Mick resents being told anything by a woman. But if anybody could tell him something it was Anita. When Anita was constructive she could really be funny. She’d make suggestions in the studio that would be half serious and half funny but they were good suggestions. You could see the hairs on the back of Mick’s neck just RISE.”

MARIANNE FAITHFULL: “When Mick was working on the words for a song, he’d go over them with me. That was something that was really very good between us, I think. And in a way, I’m quite proud of that, my contribution to that. But after a while, I got to hate it very much. And then years later I read a book about Scott Fitzgerald and Zelda, and I really identified with her. I think artists do that a lot. They use the life around them for their subject matter. And if you’re living with somebody who writes, your life will be used. They’re going to feed off of you. I eventually hated that, but at first I liked it, I enjoyed it.”

MARIANNE FAITHFULL: “Mick knew that if I had no outlets I would soon become edgy and fretful. A pest as well. It was important, too, that the relationship remain mutual and reciprocal. He taught me about black music and the blues. He played me James Brown, Howlin’ Wolf, Sam Cooke and Skip James and acted them out, danced them for me. They were incredibly wonderful sessions, where he would tell me all the things he knew and, more important, instill in me his own enthusiasms for things that until I met him I’d not even heard of. And I hope I did the same for him, with books and art and ideas. There was a mutual exchange of experience, energy. And then he became very, very involved in his work, and the work got better and better.”

MARIANNE FAITHFULL: “I do believe in inspired bursts. These things come through you. Mick was a major conductor of electricity, but this particular day the lightning struck me. A vivid series of pictures began forming in my head, and a story about a morphine addict. It was all there complete from the very beginning. I heard it in my head and just wrote it out. It was obviously a moment lived on the beam. But, as often happens with me, I didn’t really understand it. The result of this effortless creation was not to inspire the writing of more songs but the use of more drugs! I became a victim of my own song.”