ANDY WARHOL: “One of the last movies we made with Edie was called ‘Lupe.’ We did Edie up as the title role and filmed it at Panna Grady’s apartment in the great old Dakota on Central Park West and 72nd. We’d all heard the stories about Lupe Velez, the Mexican Spitfire, who’d lived in a Mexican-style palazzo in Hollywood and decided to commit the most beautiful Bird of Paradise suicide ever, complete with an altar and burning candles. So she set it all up and then took poison and lay down to wait for this beautiful death to overtake her, but then at the last minute she started to vomit and died with her head wrapped around the toilet bowl. We thought it was wonderful.”

ULTRA VIOLET: “Edie is at her height, too high to last. Born innocent, not knowing right from wrong, Edie tightropes on the edge of the vortex that whirls her into the underground sewer, the darker depths of the underworld. As vertical as is her rise, so vertiginous is her fall.”

J. HOBERMAN: “’Lupe’ is ultimately the poignant spectacle of watching a beautiful wraith reacting to her own past… In a way, the piece makes literal the celebrity’s dilemma: the superstar is trapped between her own disembodied image and the implacable, voracious eye of Warhol’s camera.”

VICTOR BOCKRIS: “Lupe was filmed in color on a December afternoon in 1965 on a very tense set at the socialite Panna O’Grady’s apartment in the Dakota. Edie was not in good shape. She had been fighting with a lot of people at the Factory, particularly Tavel and Warhol, screaming at them that their films were trying to make her look like a fool. Ronnie was as upset as Andy. No one had ever called his work perverse before. Edie simply did not understand what they were doing. Urged on by Chuck Wein and unscrewed by drugs she had been ripping up scripts and throwing tantrums like a diva. As they began to shoot, Bobby Neuwirth arrived with a handful of LSD and took Edie into a side room. ‘That was where the separation really took place,’ recalled one spectator. ‘When Bobby Neuwirth walked into Panna O’Grady’s that night. He had a fistful of acid. Sugar cubes. That Dylan group had always been great users of drugs as manipulating agents. And Andy was fuming, because somebody had invaded his domain.’ Bobby slipped Edie some acid and made a date for her to meet Dylan later that night at the Kettle of Fish.”

BILLY NAME: “Edie wasn’t happy with the way her career was progressing with Andy, but of course, she had gotten into amphetamine – crystal stuff, with me and Ondine and Brigid Polk, and that really devastated any possible career, because, you know, you would have to stay in your place and get ready for six hours.”

ULTRA VIOLET: “Edie calls me one day, screaming, ‘All my jewelry has disappeared, my diamond ring. They tell me it’s in my cold cream jar, but it’s not.’ She calls an hour later. ‘My fur coats have disappeared too, and I can’t find my long white satin evening gown and my black ostrich cape.’ Her designer clothes vanish, one after the other. She is stripped down to nothing. I call her to find out how she’s doing. She is out of control, her words are not connected. One day she alarms me when she tells me that during the night she passed out on the tiled floor of her bathroom and knocked her head on the toilet. ‘Can’t you go to your family?’ I ask her. Surely there is someone who can take care of her. ‘No, they’re worse than the Warhol crowd.’”

DAVID DALTON: “The Factory was a kind of tribe and its way of dealing with bolshy members was ostracism, exclusion, and isolation. The shunned ones came to bad ends. They danced out of windows, jumped off balconies, OD’ed. When the attention began to be withdrawn from Edie she went a little mad. Her oxygen was running out, she was fragmenting. Her crazed velocity, once seen as part of her uncanny charisma, now seemed a symptom of malfunctioning. Edie was someone who didn’t exist outside the unit, the group, the umah. She was the Queen Bee of the hive. Her power came from the collective energy, from the adoration of her drones. When her long-dormant hysteria began to surface, she gave off waves of panic.”

ONDINE: “People turned Edie against Warhol for their own devious reasons. They convinced her she was the next Marilyn Monroe. I think personally she was a great presence. But I don’t think she was the next Marilyn Monroe because she wasn’t a Hollywood type. Who would use her out in Hollywood?”

ROBERT HEIDE: “During this period I conferred with Andy about writing The Death of Lupe Velez for Edie who was anxious to play the role of the Mexican Spitfire, found dead in her Hollywood hacienda with her head in a toilet bowl. I met Edie at the Kettle of Fish on MacDougal Street to talk over the project. When I got there Edie was at a table with a fuzzy-haired blond Bob Dylan whose shiny black limousine was parked outside. I mentioned the script I was working on and Edie said innocently, 'Oh, we already filmed that this afternoon. It's in the can... in Technicolor.' Nothing was said when Andy arrived, although he did astonish me that evening by asking, 'When do you think Edie will commit suicide? I hope she lets me know so I can film it'."

DONALD LYONS: “Andy, insofar as he had a coherent philosophy, which is not very far, believed in seeing everybody and letting everybody run amok, in filming them destroying themselves and he didn’t care. He was willing to be kind, but that was as far as it went.”

JOHN CALE: “Edie was gone. She disappeared into the Dylan entourage like a strip of sunlight peeling off the pavement. Dylan’s entourage was the polar opposite of Andy’s. Leaving him for Bob was about the most painful and humiliating thing Edie could have done to Andy.”

DANNY FIELDS: “Edie was sort of extra-planetary. Like Andy. She was like one of those magic fairy people that come into your life, and then the wind comes along and sweeps them away – it could be the wind of death, it could be the wind of fame, it could be the wind of other people. It comes along and takes them back to wherever they came from.”

ROBBIE ROBERTSON: “I remember a night in New York with Edie Sedgwick, who was a friend of mine back then. I had scored a suite at the Chelsea Hotel. I don’t know how. I bullshitted the guy at the desk into him thinking that it would be good for him to give me this suite. And so Edie used to always come and hang out in my room. Andy Warhol was crazy about her. I mean, he was just so intrigued by her, and we’d be sitting there and the phone would ring and I’d answer it, and they’d say, ‘There’s a Mr. Warhol down here and he’s looking for Miss Sedgwick and we were wondering if she might be in your room.’ And Edie would be going, ‘Tell him I’m not here!’”

GREGORY CORSO: “I got on Warhol about Edie. It was at Max’s Kansas City. He happened to be sitting alone. I was with Allen Ginsberg. I said to Warhol, ‘You suck, you know that? You make these chicks into superstars and then you go off into your own thing and you drop them… literally, like that. You pick these little birds out and make superstars out of them. And look what happens to Edie!’ I really got on his ass. Ginsberg whispered to me, ‘Gregory, you’re laying too much weight on this man. It’s really not his fault. Don’t you think you should apologize to that man?’ I said, ‘No way.’”

KEVIN THOMAS: “Speaking of those ladies he has made the pop girls of the year – Baby Jane Holzer in ’64, Edie Sedgwick in ’65 and Nico, a candidate for ’66 – Andy feels that ‘Edie was the best, the greatest. She never understood what I was doing to her. I don’t know what’s going to happen to her now.’”

ONDINE: “She came back to the Factory and we tried to make a movie with her, Warhol and I, but we just wiped our hands of her, there was nothing we could do with her. How many times can you tell a person to stop doing something without really getting bored with it? I’d never seen Warhol walk away from his camera in a fit of just absolute, abject disgust but during that filming, a little movie of his called ‘Edie and Ondine,’ he just said, ‘Stop. I won’t film anymore.’ He said ‘this is disgusting, just absolutely disgusting.’ She was so full of self-pity and so humble and so everything else it was just awful, it was horrible, intolerable… She tried to make a film again because there was nowhere else for her to go. She was obviously a product of the Warhol era. She was a Warhol creation in a certain way. A Warhol creation released from its master is hopeless. Viva is not a Warhol creation. Taylor Mead is not a Warhol creation. I’m not a Warhol creation. We are creations of our own. But Edie is like a Warhol creation. She really could not do without him.”

GENEVIEVE CHARBIN: “I stayed with Edie for a few weeks, and Andy was always the last to call at night and the first in the morning. He really, really cared about her. There’s absolutely no way that anything was going to save Edie Sedgwick, let alone a screenplay. She was very far gone, right from the beginning.”

DANNY FIELDS: “Leonard Cohen was staying at the Chelsea and I brought him down the hall to the room where Edie and Brigid Berlin had been hanging out. I guess they’d been doing amphetamine because the floor was covered with jars of sequins and magic markers. Brigid had passed out onto an open jar of glue and was stuck to the carpet. She didn’t even know it, she was sleeping so soundly. But when she tried to roll over, she was glued to the carpet. Edie was blithely putting on her make-up. There was a store on 22nd and 7th, a voodoo shop, a magic shop or something. Edie was a very good customer there – or shoplifter. She had bought a bunch of candles and had put them on the mantle. ‘Oh Edie will be right out,’ I told Cohen. And he said, ‘This is a very unlucky arrangement of candles.’ Of course, I wanted to know why, but he just said, ‘I know these things. I know about magic candles.’ I can’t remember which was shorter or longer or which was fatter or skinnier. I don’t know how you can recognize an unlucky arrangement of like nine candles on a fireplace, but he said, ‘You should really tell her not to do this.’ ‘Leonard, you tell her,’ I said. ‘I’m not getting into this with Edie.’ So they met, and of course they knew to be impressed with each other. They were supposed to be impressed with each other. Then I asked Leonard Cohen to tell Edie what he’d told me about the candles. ‘Oh, it’s in the Sioux religion or the Navajo world or something,’ he said. ‘It’s considered bad luck to have this particular combination of candles.’ ‘Oh, it’s only a silly superstition,’ she replied, and the next day the room burned down.”

BOB SIMMONS: “So I will have to regale you sometime about the ‘wild night’ I spent with Neuwirth and Edie in NYC as they rolled with bumpkin me along from club to club fighting and snorting crystal all evening. I was the designated driver before there was such a concept, but I did, stupidly, maintain a car when living in the city, so… I do remember at 5 a.m. in some dive like the Kettle of Fish after a particularly bitter exchange between the two, Edie jumped up and started to stalk out without Bobby. He yelled after her at the top of his lungs for the 20 or 30 other night crawlers to hear, “Go on, leave! Fifty dollars is way too much for a cheap bitch like you.” She kept walking without looking back. I later called her up and got her to be our “SlumGoddess” in an edition of The East Village Other. Walter Bredel took the pics, and we posed her next to a TUMS poster in the subway. When we printed the neg, we printed it backwards…SMUT.”

JOHN PALMER: “We had no one to play the lead in a film we were planning called ‘Ciao! Manhattan.’ I was talking to Chuck Wein in Bob Margouleff’s office – Bob was to be the producer – and Chuck said, ‘Well, what about Edie?’ I said, ‘Sure, she’d be terrific.’ He said, ‘Oh, my God, do you think she could do it? These days she’s so spaced and stoned and wiped out.’ I said, ‘Yeah, that’s true, but we don’t have anybody else, so we might as well get her.’ So we got Edie and, sure enough, she was spaced.”

EDIE SEDGWICK: “The whole speed ravage… that was something I was very much a part of, but at the same time I was conked out on God knows how many Seconal and Tuinal and a lot of barbiturates to sort of cool the ravages of speed, that incredible nightmare paranoia that… well… it drives human beings crazy.”

EDIE SEDGWICK: “You want to hear something I wrote about the horror of speed? Well, maybe you don’t, but the nearly incommunicable torrents of speed, buzzerama, that acrylic high, horrendous, yodeling, repetitious echoes of an infinity so brutally harrowing that words cannot capture the devastation nor the tone of such a vicious nightmare.”

CHERRY VANILLA: “On Easter Sunday 1967, we had the first New York City be-in. Unlike the antiwar protests, the be-in had no stage, no speakers, and no apparent organizers, except maybe for a group called Experiments in Art and Technology that had distributed flyers and posters stating the date and location – March 26, Sheep Meadow in Central Park. About ten thousand people showed up, including Allen Ginsberg, Abbie Hoffmann, and most of my friends and me – all of us there simply to be (unless we were part of some secret social experiment we’ve yet to find out about). It was like a scene out of a fairy tale and a lovely way to celebrate spring – flower children, hippies, and Easter paraders strolling around or sitting on the grass in their pastel-colored finery, sharing their sandwiches and jelly beans, giving out daffodils and daisies, playing flutes, flying kites, and tossing Frisbees. It was blissful and magical – especially on acid, as so many of us were. Looking back, I realize how deluded we all were then, to imagine that the whole world had been spiritually awakened by psychedelics and would soon become one big peaceful, harmonious, communal garden like Central Park was on that day. But it was the very absence of cynicism that made being young and high in the sixties so especially great.”

BOBBY ANDERSON: “In the evening we’d help each other get dressed for the parties. I used to really get off on making her very fabulous and beautiful. She’d go in her boxes and crates and dig out all these things. Scarves. Jewelry. Sometimes we’d spend two days getting dressed and we’d sail right past the party we were going to.”

BOBBY ANDERSON: “At Max’s it was as if Queen Elizabeth had arrived. I remember going out with her in the afternoon when she had on what she called her mini evening gown. She’d seen a full length evening gown in the window at Bergdorf’s trimmed in egret feathers. She went in and bought it, and because the mini skirt was in such vogue then, she had the evening dress cut to mini size and had the feathers put back on. That was her mini evening gown. Over that she wore a black ostrich-plume coat, peacock feather earrings, and black satin gloves up to here with ostrich plume bows on the top. For broad daylight in the East Village she was incredible. With a huge black straw hat over it.”

DAVID DALTON: “In the spring of 1967 the infernal machinery of ‘Ciao! Manhattan,’ her final movie, cranks into gear. It’s a gruesome film, not only because of the flagrant exploitation of someone in terrible mental and physical shape, but also because it revels in her sordid state with repellant voyeurism. It tracks Edie’s disintegration with unseemly relish, getting her to undergo humiliating recreations of her shock treatments, speed shots, and utter degeneration. Edie is too drunk and pilled up to notice that she is the subject of these serial humiliations. That she agreed to undergo them only testifies to her pathetic state of mind. The smarmy abuse of someone so vulnerable and incapable of protecting herself is disturbing. Worse, its sordid point of view forces us to read her life backwards from those final mortifying scenes, in which Edie lurches from one degradation to the next.”

CHERRY VANILLA: “In 1966, I got introduced to the in-crowd’s newest elixir, Dr. Bishop’s vitamin shots. At thirty-five dollars a pop, they were pretty expensive, but one or two a day would keep you up forever and keep you looking fresh and vibrant the whole time. I forget who first introduced me to Dr. Bishop. It might have been Joel Schumaker (one of the original Paraphernalia designers). Anyway, someone had to bring you there. You couldn’t just walk in off of the street. Dr. Bishop’s office was located on the ground floor of a high-rise near First Avenue and later in a mansion at 53rd and Madison. It was a scene so quintessentially 60s, you just couldn’t even imagine a doctor’s office like it today. The clubby drug buzz in the waiting room was so dense and intense, you got high on anticipation just walking in there. The ‘nurses’ (none of us knew or cared if they were really nurses or not) wore seductively modern sportswear and often pulled down your pants and gave you your shot in the hallway, while the examining rooms might be occupied by Dr. Bishop giving someone the sixty-dollar special and/or somebody ‘having a bad reaction.’ Everyone was always in a rush, wanted to be seen first, had somewhere to be, had a taxi waiting, whatever. But once they got that shot in the ass, they often couldn’t tear themselves away from the chemically and socially charged atmosphere and would get caught up in the speed-rap session that was always going on among the patients.”

DAVID DALTON: “Edie’s nouveau hipster Dr. Robert and Brian Jones' nosferatu-like Dr. Jacobson lurking in his medieval catacombs with Jay Lerner trying to write another hit show between shots of vitamin B and methedrine… The satellite dishes planned for the roof (to catch alien whispers from space), and a heliport so his patients could get their shots and take off for the Hamptons, Washington, Xanadu. A speedfreak’s delusional plans for neocortical architecture, sonic vibrational mood rooms, rooms that breathed, rooms that rotated, black-light rooms, a scale model of the Ganges in the basement.”

CHERRY VANILLA: “Dr. Bishop had his favorite patients, especially the one male and one female he’d singled out from each sign of the zodiac. I was his Libra girl. I can’t believe I actually had a huge sense of pride about that. It meant that, along with the vitamins and speed, my shot might get an extra dose of whatever he was experimenting with that week – things like adrenaline stimulants, niacin, and even LSD. And he’d have his favorites call him about an hour after getting the shot to let him know what we were feeling. This guy was using us all as guinea pigs, and I thought he was some kind of savior, freeing us from the need for food and sleep.”

ANDREW LOOG OLDHAM: “Brian Jones took me to visit the offices of the notorious Dr. Max Jacobson, known as Dr. Feelgood because of his mysterious injections. At three, four in the morning, Brian takes me to Dr. Jacobson’s brownstone. We are ushered right in, past several people in the waiting room. I’m amazed that a doctor would have office hours at three in the morning but there he is in a dirty white smock that’s got blood spurts all over it. And on his desk are the remains of half-eaten sausages and sauerkraut, as God is my witness. There’s a line of several booths that have people in them. While I was getting jabbed, I looked in amazement at the citations that covered the walls – from the Kennedys, Lyndon Johnson, Dietrich, so on and so forth. I mean seeing those famous people was a fucking trip. And then I saw that sitting in one of those booths giving dictation, while Jacobson injected him, was Alan Jay Lerner. It blew my mind that the great songwriter was there working on a show under those weird conditions. It was no wonder he was having trouble writing new shows!”

JOEL SCHUMAKER: “Before leaving Dr. Roberts’ I’d often go and find Edie in the sauna. If we’d been up all night on drugs, the sauna and steam bath were wonderful things. We’d go out and walk for blocks and blocks… just be together, because we didn’t know what we were saying half the time.”

HENRY GELDZAHLER: “I came to her apartment a couple of times, which I thought very grim. It was very dark, and the talk was always about how hungover she was, or how high she was yesterday, or how high she would be tomorrow. She was very nervous, very fragile, very thin, very hysterical. You could hear her screaming even when she wasn’t screaming – this sort of supersonic whistling.”

RICHIE BERLIN: “I remember screaming at Genevieve Charbin. She called out, ‘Do you want me to turn the camera off?’ and I said, ‘I couldn’t care less. I intend to die in Chuck Wein’s film!’ I began to sink to the bottom of the pool… all those drugs, the sex on the raft, all the gold jewelry that Edie put on me when she went swimming.”

EDIE SEDGWICK: “Oh, wow, what a scene that place was – that heavenly drug-down-sexual-perversion-get-their-rocks-off health spa. I was already so bombed I don’t know how I got there. I got down to the pool, where all the freaks were. I met Paul America at the pool and I told him we were probably in danger if we stayed, but we were so blasted we forgot what was good for us and what wasn’t, and the whole place turned into a giant orgy… It was one of the wildest scenes I’ve ever been in or ever hope to be in. I should be ashamed of myself. I’m not, but I should be.”

VIVA: “The movie was awful. The cameraman was always so drugged up on amphetamine that he kept falling asleep in front of the camera… amphetamine is supposed to keep you awake, but he had been taking it for so many days without sleeping at all that nothing could keep him awake. We were shooting a scene in a swimming pool at a Health Club, underwater: an actor and I were supposed to make love while swimming around. By the time the cameraman started shooting, we were so cold we were blue. And, as we came out of the pool, we found that the cameraman had disappeared, all we could see was the camera. Half underwater. The cameraman was asleep, half underwater, half out, his head resting on a camera lever. The cast revived him and tried to get him to film the scene over again. But he just kept falling asleep.”

VIVA: “Meanwhile, the star, Edie, was being shot up in the dressing room; she had brought her own doctor to do the job. I told the script girl that Edie was being shot up and the script girl told me to shut up. I was shocked. It turned out that the director had arranged for the whole thing.”

HUDDLER BISBY: “Edie’s success as a drug geisha was based on her ability to handle high-speed drugs at high speeds… at very high speeds. Difficult to do. The secret of her charisma was that she was only really beautiful when she was running not just at fifteen miles an hour, or fifty, or eighty-eight, but at fifteen hundred.”

ONDINE: “Contrary to the opinion that drugs killed Edie, I think it was ‘Ciao! Manhattan’ that killed her. I really do. I think that when she saw it on screen she realized she was washed up. It may have been the reason why Edie had a long slow suicide.”

GERARD MALANGA: “How she ended up sequencing into John Palmer and that awful ‘Ciao! Manhattan’ movie guy [David Weisman] I don’t know. I was out of the loop on that. She was a sweetheart. And got taken advantage of by a lot of people and it just went on and on till the day she died.”

NICO: “While I was at the Castle I looked after Edie who had joined me. She was still so beautiful, but she had a problem with heroin then. She told me to be careful of Andy because he would use me to get more famous and then forget me when he wanted… She was my warning.”

DAVID DALTON: “Communion with her sad photographs allows her acolytes to experience the rush of transubstantiation: a flashing pulse of energy as the filaments ignite in unadulterated narcissism, drug high, and pure childlike joy… She is their fucked-up martyr, an anti-saint of transgression and wretched excess. The world is bullshit, the bravest approach is to simply malfunction. Fucked-upness means you are healthy – all else is phoniness and rationalization. Edie’s disciples make a fetish even out of her vacuity. She’s hallowed for a kind of absence, a hollowed-outness, an extraterrestrial void that generates fierce attractions. Even her neurasthenia and her fragility are seen as emblems of her peculiar grace. An elfin creature who defied the laws of logic, gravity, and common sense in pursuit of something so trivial and ephemeral it seems almost mythical… her image beams to us from somewhere out there, as she goes on talking to herself endlessly, smoking cigarettes through all eternity.”

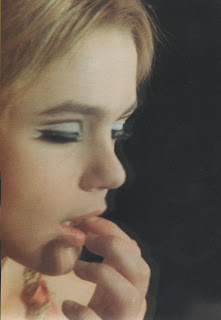

MINDY LEWIS: “One day a real celebrity arrives. Edie Sedgwick, Andy Warhol’s superstar, famous for her poor-little-rich-girl presence in his films. Edie has an appealing, dreamy spaciness, a waif fallen from the society pages to the druggy avant-garde art world. She is stick-skinny, hipless and flat-chested, swimming in the big T-shirts she wears as mini-dresses over black tights. Her blond hair is in a tousled, two-toned pixie cut. Her eyes, accentuated by black eyeliner and false eyelashes thickened with black mascara, are like headlights. Even without makeup, she’s luminous. Edie’s life has been filled with mixed blessings. She’s survived over-doses, fires, and other bad scenes… Right from the start Edie brightens up the ward. Every morning she spreads her blanket out on the floor and practices yoga, gracefully bending her torso over her legs, then straightening, lifting her head like a sunflower on a skinny stalk. ‘I love doing my exercises,’ she says. ‘My best thoughts come to me when I do yoga. It gives me a glow.’ She tells us she used to mainline heroin. There’s nothing like it, she says, like a blissful, soothing snowfall, better than sex. The only thing is that she overdoses all the time. In her attempts to recapture the bliss of her first experience, she always does too much.”

JOHN ANTHONY WALKER: “I don’t care what she did or how wrong she was. She was a catalyst, what is known as a shakti in the trade. The female energy which dynamizes: by being in contact with her, the edges were sharper. An evening with Edie would only end when Edie had got to the point of exhaustion, which would be at the end of two or three days. There’s that old Yogi axiom: the higher you go, the further you fall. We all know that. She liked walking very close to extinction always. Edie had a very hard time handling the world… as would be the case with an Olympian god who had taken the wrong exit off Olympus and come down here into this mortal coil.”

NICO: “Some things you are born to, and Edie was born to die from her pleasures. She would have to die from drugs whoever gave them to her... You either live outside or inside, and some drugs help you to live inside. Edie Sedgwick wanted to live inside because there was nothing outside for her to see anymore. But she was a husk. She died because there was nothing inside, either. Brian Jones died because there was too much inside. They died the same age, you know.”

ULTRA VIOLET: “I am especially troubled by Edie. I am obsessed by her memory, a bright morning star, and I let her waste away. I saw her turn to dust. Could I have prevented her death? Am I my sister’s keeper? Alone and in torment, I think of Edie. In my sane mind I know I was powerless against the forces pulling her to destruction. Neither logic nor love can save a person possessed by drugs. But still the doomed Edie haunts my weird, flickering dreams, dreams of hellfire, racks, and torture devices that punish me day and night.”

EDUARDO LOPEZ DE ROMANA: “Some people search hard, you know. You can search with nature, you can search with your mind, you can search with your body, you can search with chemicals, you can search, and that’s what we’re talking about. Is that, the dynamo, the engine that makes things move? Some people search and they search tough, they search hard, they search with their body. There’s hunger. There’s anger. There’s angst. There’s thirst. And a person like Edie, I suppose, is given every benefit of that whole generation… of that whole nation in conquest and in victory and yet there has to come an apogee; you get as high as you can and you can’t get any higher.”

DANNY FIELDS: “When I knew her she was not of this earth. She was, indeed, never of this earth. She was born of madness and suffering and declined into madness and suffering. But she had a period when the sun shone for her, when life was smiling. And she was smiling with it.”

ANONYMOUS: “Where is she now?” I ask Billy Name. “Oh, up in the silver clouds,” he sighs. “She’s just an angel.” “Is she bored?” “Nah, she had a life within her.” “How do you remember her?” “I picture her sitting on the sofa with her legs crossed, being delightful and chatting about pretty things.”

PATTI SMITH: “On a cold November afternoon in 1971, Bobby Neuwirth called me at the Chelsea Hotel. "The lady's dead," he said, and he seemed genuinely sad. "You're a poet; write her a line," which I did. I sat in Room 1019, which belonged to the artist Sandy Daley. It was a huge white room with white floors. Two of the original helium silver pillows from the Factory floated freely through the room. I wrote Edie a poem. A girl I never knew. She was only three years older than I, and she was dead. Young. Electric. Talented. Dead. This was my initiation into the world of drugs, as much as any drug experience seeing secondhand the destruction of a human being. She was just a shooting star. Her white light illuminated Manhattan. She provided us with one of the exciting, energetic images of the sixties. But at what cost? The mischievous-faced poor little rich girl who elevated the word "cute" into art was gone. Whether she pawned her diamond rings, I do not know. She certainly fit the description of the Miss Lonely of "Like a Rolling Stone." But she would never be back to claim her goods. Her furs or her jewels. She was a rural girl's entrance into the cream of our culture. My first image of her is the one I like to remember. In Vogue. No drugs. No fame. Just an ermine-haired girl in black tights with perfect balance.”