STEVEN WATSON: “Tom Wolfe’s ‘pariah fashion’ was born not in the bastions of wealth or traditional chic but in the black subculture, from homosexuals, even working-class south Florida. Baby Jane Holzer could survey this gaudy smorgasbord of bouffants, stretch pants, French thrust bras, brush-on eyelashes, outsize beehives, and elf boots and exclaim, ‘Aren’t they supermarvelous?’ No one epitomized that particular kind of New York anything-goes glamour better than Holzer. A queen of underground film, she was at home in what Wolfe discreetly called the world of high camp or mixing with Park Avenue millionaires.”

TONY SCHERMAN: “Jane Holzer, the former Jane Brookenfeld of Palm Beach, Florida, now ‘Baby Jane’ to every gossip columnist and feature writer in New York City, a Park Avenue socialite (but definitely not of the old order), who, with her coltish, twenty-four-year-old’s enthusiasm, embraced Lower Bohemia more avidly than any of the other new Pop socialites. When Warhol met her in 1963, she had already embarked on a modeling career, more or less as a rich girl’s lark; in Swinging London in the summer of 1963 she had been transformed almost instantly into a highly sought-after cover girl.”

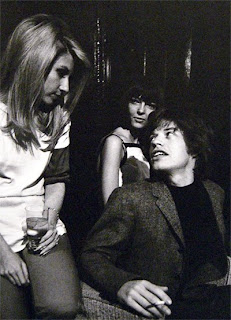

VICTOR BOCKRIS: “With her leonine mane of hair, the latest in high-style clothes, and her friendship with the Rolling Stones, this beautiful Park Avenue socialite, the wife of a wealthy businessman, had been thrust into the fashion spotlight by the British photographer David Bailey and been profiled by Tom Wolfe as the ‘Girl of the Year, 1964.’”

BABY JANE HOLZER: “Wait till you see the Stones! They’re so sexy! They’re pure sex! They’re divine! When Mick Jagger comes into the Ad Lib in London – I mean there’s nothing like the Ad Lib in New York. You can go into the Ad Lib and everyone is there. They’re all young and they’re taking over, it’s like a whole revolution, I mean, it’s exciting, they’re from the lower classes, East End sort of thing. There’s nobody exciting from the upper classes anymore.”

TOM WOLFE: “That girl on the aisle, Baby Jane, is a fabulous girl. She comprehends what the Rolling Stones mean. Any columnist in New York could tell them who she is… A celebrity of New York’s new era of Wog Hip… Baby Jane Holzer. Jane Holzer in Vogue, Jane Holzer in Life, Jane Holzer in Andy Warhol’s underground movies, Jane Holzer in the world of High Camp, Jane Holzer at the rock and roll, Jane Holzer is – well, how can one put it into words? Jane Holzer is This Year’s Girl. New York’s Girl of the Year – Baby Jane – is the most incredible socialite in history. Here in this one girl is the living embodiment of almost pure ‘pop’ sensation, a kind of corn-haired essence of the new styles of life.”

MARY WORONOV: “These rich people who could come down to the Factory, to slum… The value thing was shifting. The top was coming down to get something. We had the power over them. We were just a bunch of smart queers, some of whom weren’t queer, and amphetamine heads, smart but bored, who understood that this guy’s like a mark. He’s an audience. And we played it.”

ULTRA VIOLET: “Baby Jane Holzer, a genuine Jewish-American princess, vaguely reminiscent of the divine, inimitable Brigitte Bardot, has lots of long blond hair, lengthy legs under a miniskirt, a forced smile, an air of playing at femininity and voguishness. She takes a teasing comb out of her clear plastic makeup bag and puffs up the back of her hair. With a red lipliner, she reinforces the outline of her kissy mouth. She blots her lips, puts on more crayon, blots again, pales her lips, blots again, pales again, in a ritual gesture. Her walk is that of a model on a runway. When she speaks, she swings her long blond hair from one side to the other. Her voice sounds smooth and practiced. She asks, ‘Oooh, what’s happening, aaaah?’ but no one hears her over the thunder of Stravinsky’s ‘Petrouchka.’ She goes back to her mirror. A dropout from fashionable Finch Junior College, she wants you to understand that she is very contemporary and quite gorgeous. Between two sniffs of white powder, Eric Emerson glances at her and says, ‘A straight jerk, that Baby Doll.’”

BABY JANE HOLZER: “Some people look at my pictures and say I look very mature and sophisticated. Some people say I look like a child, you know, Baby Jane. And I mean, I don’t know what I look like. I guess it’s just 1964 Jewish.”

KEVIN THOMAS: “’Jane wants to make it so bad and Hollywood could make her terrific. I don’t understand why she hasn’t made it already.’ When it was suggested that maybe Jane was so complete a creation that there was nothing left for Hollywood to mold, Warhol disagreed. ‘That should make her double-terrific.’”

BABY JANE HOLZER: "I remember it used to be so embarrassing in the '60s: he and ten people would show up and crash. By the '70s, he was the first one to be invited anywhere."

ULTRA VIOLET: “Andy was always an observer, but he was also a taker. In other words, he seemed to be very detached, and not involved, yet if there was a pretty boy in the room he would spot him immediately. The Factory was a fishing ground for Andy, for movies and for everything, because Andy was interested in everything, he capitalized on everyone. He had charisma. He had magic. He was like Hitler, in fact. People were drawn to him, they couldn’t resist.”

ANDY WARHOL: “In those days, everything was loose, flexible. The people in the studio were there night and day. Friends of friends. Maria Callas was always on the phonograph and there were lots of mirrors and a lot of tinfoil. I worked from ten a.m. to ten p.m., usually, going home to sleep and coming back in the morning, but when I would get there in the morning the same people I’d left there the night before were still there, still going strong, still with Maria and the mirrors.”

BILLY NAME: “The denizens of the Factory knew that Andy knew that the life they lived was in some way fabulous, and that he was there to garner some of it, if he could. He had access to something other filmmakers didn’t. They only had professional performers and actors, trained and scripted. Whereas he had access to the so-called fabulous world of brilliant minds and sayings, and that was something that he realized could be uniquely his portrait.”

BABY JANE HOLZER: “It was getting very scary at the Factory. There were too many crazy people around who were stoned and using too many drugs. They had some laughing gas that everybody was sniffing. The whole thing freaked me out, and I figured it was becoming too faggy and sick and druggy. I couldn’t take it. Edie had arrived, but she was very happy to put up with that sort of ambience.”

VICTOR BOCKRIS: “Ivy Nicholson, a fashion model who had been at the Factory since 1964, was so desperate for attention that she had begun making noises about ‘marrying’ Andy. On one occasion, when Ondine went over to her apartment, she opened the door and threw a cup of hot coffee in his face. Another time, after Billy had ejected her from the Factory, she left a pile of her excrement in the elevator.”

DANNY FIELDS: “The first time I met Andy Warhol – on that particular day, during that particular twenty-four hours – he was extremely famous because his Campbell Soup cans had made it to the lead story of the New York Times. When I arrived at the party, Andy was sitting on the couch with Gerard Malanga and Ivy Nicholson. And Ivy was getting drunk and started crawling across the floor to Andy on her belly. She sort of squiggled across the floor and started pawing at Andy’s leg – rubbing his knee – saying, ‘Oh, Andy, I love you. I love you!’ I don’t know if she said, ‘Put me in a movie,’ or not. She probably did. She probably said, ‘I love you, comma, put me in a movie.’ And Andy tried to kick her away with his foot – his leg was crossed – and every time she would rub his leg, he would sort of kick her off like, ‘Go away!’ She was like an annoying pet, like a dog who was trying to hump you. So Ivy went over to the window – she let down the top sash – then she climbed up on the windowsill and she put one leg over. Then she stuck her head out. And then she put her arm over- she was going out the window. Everyone else was sort of watching her, but I was nervous because she was going to jump. So I went over to her and I said, ‘Don’t do that. You mustn’t do that, come back inside, everything will be all right.’ So she came back inside, and I thought people would say, ‘Oh, aren’t you a hero, you saved her life.’ And Andy says, ‘Oh, why did you do that? Why didn’t you let her jump?’ And I thought to myself, Oh, these people are much cooler than me.”

MARY WORONOV: “Andy thought if people didn’t work they were broken, something was wrong with them. ‘Why can’t you model too, we’ll take photos of you and you’ll be famous like Ivy,’ he nagged. Nobody could whine like Andy, he invented it. Anyway, all I ever saw Ivy do was take a dump behind the silver couch. This crazy woman wanted to marry Andy Warhol, which meant getting as close to him as she could or leaving a piece of herself with him. She definitely did not have all her oars in the water; if you asked me she didn’t even know what an oar was. Sometimes Gerard would have to fend her off, or Billy would be called to throw her out of the Factory. Later the elevator would return empty except for a single lonely turd, and someone would snicker, ‘Andy, Ivy’s back.’ Yeah, if she could model, I should be getting the Oscar any day now.”

ANDY WARHOL: “This is when I started realizing how insane people can be. For example, one girl moved into the elevator and wouldn’t leave for a week until they refused to bring her any more Cokes. I didn’t know what to make of the whole scene. Since I was paying the rent for the studio, I guessed that this somehow was actually my scene, but don’t ask me what it was all about, because I never could figure it out.”

ANDY WARHOL: “So Ivy called me up and said, ‘I’m going to Mexico right now and, you know, can you give me some money? I’m getting a divorce and I’m coming back and marrying you,’ and I said,’What?!’ I can’t figure out what she really, really wants.”

ANDY WARHOL: “I bought ‘People’ magazine and there was their article about Ivy Nicholson – she’s now a bag lady in San Francisco. She looks like the most beautiful bag lady you’ll ever see, though. She’s up against the wall with her legs straight out and a form-fitting top. Everything just looks right when she does it, so it’s these raggy clothes, but they look great.”

IVY NICHOLSON: “When I left Andy had to replace me with drag queens. I would have been his wife. He was going to ask me. That was during my homeless period. I got more publicity when I became homeless than when I lived in my first husband’s castle.”

ULTRA VIOLET: “I met Salvador Dali, and we had a very long friendship that lasted five years. One day Andy Warhol came for tea, with Dali, and that’s when I met Andy. It was a lucky strike. He was one of the most interesting – famous is beside the point – artists in America. Andy said, ‘Let’s do a movie.’ I said, ‘Fine, when?’ And he said, ‘tomorrow.’ So I went to the Factory the next day. I wasn’t Ultra Violet when I met Andy. My real name is Isabella Collin Dufresne. It was too hard to pronounce and remember. After I did my first movie, Andy said, ‘We have to find a name.’ ‘No thanks,’ I said, ‘I’ll find my own.’ That night I was reading an article in Time magazine on light, which fascinated me, and they mentioned ultra violet. I thought that was a great name. It just popped out of the page, and I told Andy.”

ULTRA VIOLET: “Once I adopt my nom de plume, or better yet, nom de guerre, I have to live up to it. My first aim is to upstage all the other superstars. It is not my nature to be one of a crowd. I must stand out. My name gives me a head start. I can be ultra anything. But first, of course, I have to begin with the color. That means my collection of dark brown wigs, which I wear to dramatize certain outfits or to substitute for a trip to the hairdresser, is turned over to a theatrical beautician, who dyes them various shades of violet. I mean violet – not modestly lilac or sweetly mauve. Violet. You can’t miss me in a mob. To renew my lip color during an evening I pull out of my gold mesh evening purse a gigantic fresh beet with the green leaves still dangling on their red stems. With a tiny gold knife I slice a morsel from the beet and rub it on my lips and cheeks in full view of the staring onlookers. The shade it imparts is neither red nor pink nor orange but an out-of-this-world rouge-violet. Try it sometime.”

JOHN CHAMBERLAIN: “I had some great love affairs… starting with Ultra Violet. Americans don’t meet many people like her, very French. She wasn’t very difficult to look at, either. I sort of liked all those Factory people of Andy’s. Theirs was always the right shade of craziness.”

BOB BRADY: “The first time I met Ultra Violet somebody said, ‘See that girl there? She was Salvador Dali’s lover.’ Then the next thing I knew, she was Chamberlain’s lover, then Ed Ruscha’s lover. She was actually gorgeous.”

ANDY WARHOL: “Ultra Violet was still a big mystery; nobody knew what her scene was – she kept her life very secret. I’d met her one day in ’65 when she walked into the Factory in a pink Chanel suit and bought a big Flowers painting that was still wet for $500. She had expensive clothes and a penthouse on Fifth Avenue, and she drove a Lincoln that was the same as the presidential one. She was past a certain age, but she was still beautiful; she looked a lot like Vivien Leigh.”

ULTRA VIOLET: “Here my rebellion is accepted, even encouraged. They wouldn’t tolerate me if I weren’t rebellious. What’s more, my rebellion is getting attention from the press and I love it. I love seeing my name and my picture in the press and the magazines. I feel I am at last getting the love and attention I’ve always wanted. If need be, I’ll be crazier than the others, bolder, more daring, to keep eyes and cameras focused on me, me, me.”

ULTRA VIOLET: “Some people send me violets for every occasion. Bouquets of them come from known and unknown admirers. I keep them all. When they dry, I tape them to the frame of my front door. Their color turns to dark amber-rose with streaks of mauve. The door becomes a magnificent floral archway. It’s the closest I get to nature in New York City.”

TONY SCHERMAN: “As David Bourdon put it, Ultra Violet’s most remarkable gift was ‘a sixth sense for discovering photo opportunities.’ Seeing Andy and one of his superstars posing for a photographer, Ultra would squeeze into the picture, just to their right; that way, she’d be listed first in the caption. Ultra Violet was shortly to develop a mini-career speaking for ‘the underground’ on TV talk shows such as The Merv Griffin Show. This tickled authentic undergrounders to no end, since they’d never laid eyes on this self-proclaimed spokesperson. ‘She’d tell journalists ‘I collect art and love,’ Andy said. ‘But what she really collected was press clippings.’”